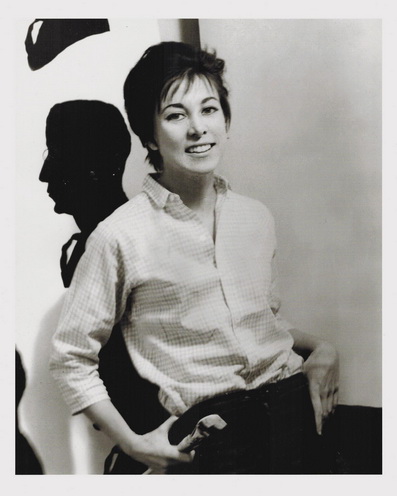

© Estate of Idelle Weber |

Idelle Weber | |

| Birth Date: March 12, 1932 |

||

| Death Date: March 23, 2020 Artist Gallery |

||

| Idelle Weber was born in 1932 in Chicago, Illinois and was adopted a year later. When she was nine years old, her family moved to Los Angeles, California, where the private art collections of neighbors fueled her passion for visual culture. Her family fostered her interest in the arts at an early age, often taking her to museums and purchasing art supplies and equipment for her, such as her beloved camera and oil paints. This encouragement to pursue art sparked a lifelong passion; she would frequently ride her bike to an art gallery with her artwork in tow to ask for constructive criticism.

Weber always had an eye for detail, her camera and magnifying glass anticipating her lifelong practice of close observation. She would also collect newspaper clippings and comic strips, foreshadowing her eventual focus on pop culture and commercial imagery.

After graduating high school, Weber received a full scholarship to study art at Scripps College, though she would soon transfer to UCLA where she earned both her BFA and MFA. While at UCLA, she was the only woman artist in her cohort, but soon paved a way for herself within the male-dominated art world she would come to know so well.

Weber moved to New York City in 1957 after one of her charcoal drawings was accepted into a MoMA exhibition titled "Recent Drawings USA," where she met Josef Albers, Mark Rothko, and her future husband Julian Weber. Regardless of being in the same social circles as these men and working just as hard, Weber faced countless instances of sexism and exclusion, mainly from the male artists, historians, and gallery owners she encountered who were unwilling to include women in their exhibitions, catalogs, and classes. One such rejection occurred when an art dealer told Weber, “I don’t [exhibit] women…they get married, and they have children.” Throughout her career, Weber would hear this repeatedly from various men, including artist Robert Motherwell, who refused her entry into his class because she was a woman.

During the mid to late 20th century, it was considered unusual for women to be career-driven. Weber was an outlier, proving that women could be mothers while simultaneously focusing on a career. Throughout her life, she successfully juggled her roles of wife, mother, and artist, carving out schedules to paint, and strategically hosting studio visits for gallery owners during her son’s naptime. However discouraging these experiences must have been for Weber as a young artist, she continued to fight for equality in these male-centric spaces. In her tireless pursuit for gallery representation, she eventually found it at Bertha Schaefer Gallery — run by a female designer.

Weber’s first two solo exhibits at Bertha Schaefer Gallery in 1963 and 1964 established her as one the few women in the newly defined Pop Art movement. She was exhibited alongside Warhol, Lichtenstein, Wesselman, et al., in many of the groundbreaking Pop exhibits of the 60s, yet would later find herself excluded from its history — in the 1970s, her friend, Lawrence Alloway, did not include her (or any women) in a major survey of American Pop Art at the Whitney, causing Weber to destroy a large number of her Pop canvases in anger.

Weber’s Pop work primarily focused on corporate silhouettes set against brightly colored backgrounds or grid designs, something she had experimented with since the late 1950s. In these works, she intentionally reduced these figures to silhouettes in order to create distance between the viewer and the subject, and to imply standardization and commercialization of these anonymous figures. The silhouetted figures are both representational and abstract, commenting on the lack of individuality in corporate culture. By making the figures anonymous, they are universal, allowing a viewer to occupy any of the roles. They also cast a critical eye on mass culture, gender roles, sexism, and the power structures of many of these corporate spaces, often featuring imposing, powerful men and female secretaries. She also experimented with three-dimensional sculptural forms, incorporating her silhouetted forms onto materials like plexiglass and lucite. Weber created a niche for herself within the Pop art genre, focusing on the social roles created through consumer culture and corporate life, expanding the limits of what Pop art could be.

In the late 1960s, Weber shifted her discerning gaze to the streets of New York City, depicting its storefronts, fruit stands, and trash. These works are meticulously detailed, capturing a cropped-in, unique vantage point of the clutter that we would normally disregard. They provide a fresh perspective on the beauty and decay of urban life, encouraging the viewer to look at everyday objects in new ways. Inspired by her Pop art era, her trash works offer a critique on issues such as consumer culture and commercialism by focusing on everyday objects and their logos. Her skill caught the attention of gallerists who would go on to represent the majority of artists eventually coined as Photorealists. Unlike other Photorealists, Weber differed from her peers in that she never used grids, hard edges, or airbrushes in her work, which led her to be described by an art critic as “the most painterly of the Photorealists.” With her achievements in this genre, Weber once again became one of the few women recognized in a major arts movement.

Starting in 1974, Weber earned a faculty spot at Long Island University, Harvard University, and New York University. In the 1980s she found a new muse, painting large-scale, geometric views of gardens. In these works, she continued to offer zoomed-in perspectives of blades of grass, flowers, and pebbles, proving that she never abandoned her eye for detail. She returned to her trash paintings in the 1990s, this time juxtaposing the trash with the natural landscape rather than the streets of New York City.

In the late 00s, Weber was contacted by curator and art historian, Sid Sachs, about his upcoming exhibit on the women artists of Pop. Sachs recognized that a group of groundbreaking women artists had been entirely written out of its history. Weber never gave up her extraordinary eye for detail, continuing to create and exhibit work into the 2010s. Recently, Weber has begun to receive the recognition she has long deserved for the strides she made for herself as a woman in the art world, and as a pillar of Pop art and Photorealism. From her early silhouette works to her photorealist paintings, she poignantly reflected American life and culture.

Weber’s work is increasingly being exhibited and collected, found in the following public collections (among others):

Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts, Little Rock, AR

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL

Boise Art Museum, Boise, ID

Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY

Buffalo AKG Museum, Buffalo, NY

Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA

Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, DE

Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines IA

Fogg Museum of Art, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

Harvard University Collection, Fog Cambridge, MA

Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL

LACMA - Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA

Lyman Allyn Museum of Art, New London, CT

McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, TX

Melbourne University, Victorian College of the Arts, Melbourne, Australia

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY

MOMA, New York, NY

National Academy of Design, New York, NY

National Museum of American Art, Washington, D C

Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO

Portland Art Museum, Gilkey Center for Graphic Arts, Portland, OR

San Francisco Museum of Art, San Francisco, CA

Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara, CA

Sheldon Museum of Art, Lincoln, Nebraska

Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS

Smithsonian Museum of American Art, Washington, DC

Tacoma Art Museum, Tacoma, WA

Virginia Museum of Fine Art, Richmond, VA

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY

Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT

|

||